Food is often a topic that gets people very heated in debate. We eat it at least 2 times a day (sometimes 5!), it is essential for survival and it often shapes an incredibly important part of our social fabric: celebrations, artisanship, family time and caring for loved ones. Equally so, when we speak of the sustainability of our food system and the solutions to our food shortage, people are quick to opine and make big concluding statements on food affordability, availability, GM, organic certification, industrial food production, bio-tech, hydroponics. The list goes on. What is happening to our food system?

Many years ago I watched a compelling documentary called Food Inc that made me question how we build solutions to our food problems. The documentary showed an example of how a company found a solution to a recurring problem: e-coli in beef meat. E-coli is a substance created in the cow’s gut that, for whose eating its meat in quantity, can lead to death. The e-coli was said to be produced in a cow’s stomach in part due to the cow’s diet: cows are often now fed corn as opposed to the original grass-based diet, to fatten cows more quickly at a relatively inexpensive (and government subsidised) price. Apparently the problematic presence of e-coli could be resolved by allowing the animals to eat a plant based died for a week before butchering. Instead of taking a step back to avoid the problem altogether (e-coli due to corn-based diets), a company invented an industrial solution to removing the e-coli: washing the meat in ammonia. The final ’safe’ product was a pink slushy paste, that was then used for burger patty production. This struck me as crazy – we had reached a point where it was economically cheaper and better to over-engineer an additional technical step as opposed to simply scale back corn-based diets for a single week before butchering. It struck me that we weren’t solving the original problem at source, we were finding a patchy solution with unknown health consequences that was even leading to a bad-quality product (who wants slushy meat washed in ammonia?). That was the market’s solution. I started doing some research: there must be a different way.

Over the years, being an avid food lover and being concerned with issues of food sustainability in my work, I’ve come to see some creative and powerful alternatives to our current way of producing and thinking about food. I think sustainable (and non-industrialised) food production that is in harmony with the environment is not only effective, it is a necessary part of the solution. Simple, small and slow presents a compelling alternative to our current food production systems: often however seen with scepticism, I hope to break some of this down and shed some light on opportunity over the following blog entries.

PART 1. CHALLENGES OF OUR FOOD SYSTEM.

So, what is this the deal with food shortage? Currently, almost a billion people suffer from hunger due to food shortages: 1/9th of our global population is said to be clinically malnourished. Some of this is due to conflict but in most areas this is due to seasonal lack of availability: food runs out before the next harvest. And yet our population is still growing. It’s expected that an additional 2.4 billion by 2050 will have to be fed and will share the same limited resources on our planet, a 33% increase. Almost all of this population growth will be in developing countries who, with a rising middle class, are changing their food habits with an increase in demand for meat and dairy, products which require significantly more natural resources to produce. Adding to that demand, the increase in bio-fuels will put stress on the need to produce more grains. FAO’s chilling estimate is that by 2050 we will need increase food production by 70% (based on 2005-07 levels).

We must produce more food, is the obvious answer. To tackle this, our food system has taken multiple turns. For the most part, it has evolved into a powerful industrial global system. Technological innovation, opportunity for profit and also the rising demand for food range availability has created an elaborate global food supply chain. Let’s explore a couple of these trends:

- Complex, long-supply chains. Consumers have become more demanding (and food traders have seized an opportunity): we can now find almost anything we want, anywhere in a global megacity, at any time: whether it is exotic fruits, fresh fish from arctic waters or italian-made burrata. Companies not only import and export food across continents, but have been able to adapt with technology so that distance and ‘lead-time’ obstacles have been overcome. Take the banana supply chain, which has developed incredibly complex systems to get them in a store when ripe just at the right level. Bananas are picked and shipped still green, stored in large warehouses in the country of destination and then they go through a ripening chamber where, sprayed with ethylene gas – an ageing hormone – they become ready to go to a supermarket. The ethylene content is so strong that you’ll notice banana triggers ripening or rotting in other fruits it comes into close contact with or with which it is stored in a fridge. The complexity of the supply chain has driven the industry to be structured around a single banana variety: the Cavendish. All fridges, transportation systems and ripening chambers are based on this single variety’s characteristics. This has made it significantly vulnerable, where the risk of a single disease strain wiping out the whole stock is a significant threat. Fortunately for bananas, the ageing hormones haven’t affected flavour and nutritional content too much, but that cannot be said for other fruits. Other ethylene-matured fruits such as tomatoes and peaches significantly lack flavour compared to those ripened on the plant. More notably with apples, the average apple you will buy at a supermarket is extremely nutritionally weak. Known to lose most of its anti-oxidants and vitamin C within 2-3 months of being picked, the average supermarket in the UK or US will sell apples that have been stored between 6-12 months. (Check out the Guardian’s analysis on how fresh your fruit is). It’s sobering to learn the details behind our food production and the consequences we are only beginning to discover.

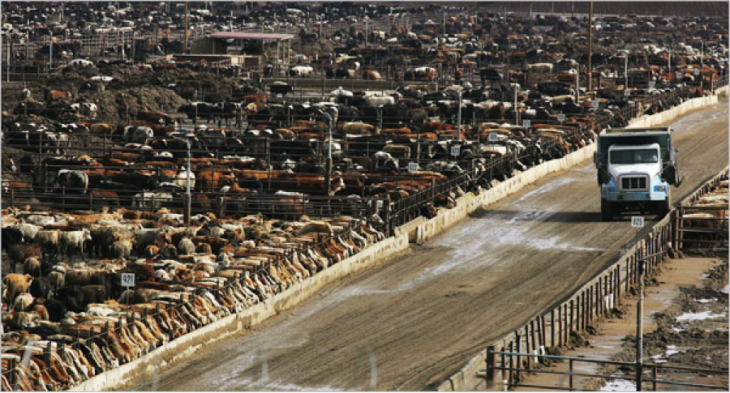

- Mass food production. In a similar vein to banana production, industrialised food production has grown immensely to produce more, more quickly and distribute more efficiently. Perhaps the most contentious form of industrialisation is that of livestock, which has reached enormous scale. Take beef production in the US: the market is mainly made up of only four companies: Tyson, Cargill, JBS and National Beef, with slaughter rates of 28,000 cows a day. The mass scale of beef production has led to shocking practices: thousands of cattle in confined spaces with little space to move and often resting in their own feces, the abuse of antibiotics to prevent the spread of disease which is raising concerns of antibiotic resistance in human populations, the use of growth hormones that has potentially altered human growth patterns, the presence of significant amounts of pus due to infection in the meat that we buy, to just name a few. A recent expose in the UK has investigated one of the chicken industrial plants responsible for 30% of UK poultry production, discovering how quality standards are not always adhered to. Chickens are gassed in mass and then go through a complex conveyer belt to be processed. Often quality loopholes are such that chicken well past its due date or that has been rejected by a supermarket for poor quality will be unpacked, replaced on the conveyer belt and re-labelled. The consumer backlash in this case has been strong, with a huge rising trend in vegetarian and vegan diets as a boycott to these industrial practices. In the US alone, vegan food consumption has increased by 600% in just the last three years.

- Bio-tech, pesticides and fertilisers. Technological innovation in food has long boomed. It brought about the ‘Green Revolution’ in the mid 20th century that was credited for substantially increasing food supply through the use of new crop breeds, fertilisers, pesticides and mechanisation. Fertilisers have increased yields by 10-70% by increasing the nutritional content the soil and preventing crop-specific pests from damaging a harvest. However, there is substantial evidence that these have had equally negative effects on our soil in the long-term, depleting it of organic life and nutrients, leading to a lack of productivity and infertility. Pesticides also pose a health hazard to the farming population who administer them, where significant rises in cancer rates have been attributed to close contact with the chemicals. Certain pesticides are also deemed responsible for the Colony Collapse Disorder, causing in certain cases the death of up to 80% of bees and other pollinators. This ironically puts an enormous strain on our ability to grow food and shows how the solutions we’ve developed for “more, faster” is in the long-term having the opposite effect. 70% of our food crops rely on pollination for their reproduction, this begs the question: what will happen without bees? And yet again we see over-engineered solutions emerging that don’t solve the root cause of the problem: instead of banning the use of these pesticides (bans have only taken effect in the EU), the use of robot bees is being explored so that the ‘ecosystem service’ that nature is providing can be replicated. Imagine the resource footprint of that robot bee…

Worryingly, there is a trend of over-engineering solutions as opposed to going back to first principles, rethinking the problematic and designing a better solution that builds into it the years of learning and discovery we have made on the side effects of the food industry. But a few creative companies however have started to find alternative solutions…

It is indeed very challenging. The World Resources Institute also created 18 graphics to address the problem : http://www.wri.org/blog/2013/12/global-food-challenge-explained-18-graphics

Furthermore, a challenge is the increase in population, as well as the change in diet. For example, in the South Pacific, locals who had eaten fish and fruits for centuries, are now eating like Americans. The result is also in increase in diabete and other diseases. I wrote an article about this a few years ago. http://cimsec.org/naru-lesson-in-failure/14205

The problem was not due to supermarkets’ strategies but to the economical growth of the country.

Finally, I was very shocked to read about the apples being stored so long. Do you happen to know why?

LikeLike

Hi Alix, Yes the case of locals who evolve out of their nutritious local diet towards worse, processed, western-modeled ones is a big thing. Take the Greenland Innuits (eskimos), who used to eat whale meat and now due to the influence of processed food shops and TVs they only want to eat burgers, with the consequence of obesity but also lack of nutritional stamina to survive the cold Arctic winters. How do we solve this is my question? I have a few ideas (next blog) but how do we not fall back into these traps of eating processed industrialized food. The media plays a big part. Can we persuade the media to value local food and culture? Do we put a limit to advertisement on unhealthy food products?

LikeLike

Thank you Francesca and look forward to next weeks edition! Wow this is so sobering to read. Meat washed in ammonia… fruit artificially ripened and months old… wondering if we are eating food at all?! Aside from the environmental concerns, I wonder how this is going to play out on our health. The same could be said for plastic being ingested by fish – plastic is now truly on the menu as a result.

LikeLike

I know. It is quite sad. It does tempt us to return to eating simple, local, farmers market. The smaller the supply chain the better it is on some ingredients. There are plenty of alternatives! Just requires being aware and thinking about it. I wonder what it is like in China though – is there an equivalent of a “local farmers market” or grocery store that sidesteps the supply chain of a big supermarket? At the moment I am here exploring agriculture in Ghana. Local food outside of the big towns is amazing – fresh produce, cooked well, etc. As soon as you’re in the towns, it’s stale ultra-processed white bread, sausages that god knows what they have in them, etc.

LikeLike

Talking about Plastic, yes indeed. Microplastics are taking on a whole new dimension. Not just in terms of bits of plastic bottles that are injested from the ocean, but for example the plastic dust particles that comes off of our synthetic clothes, which is almost invisible but that is what most of our “dust” is made of, small plastic particles that we are continuously breathing in. Apparently, if for example you are at a conference, you can estimate the amount of “microplastics” being released into the air as you speak by people’s clothing. The Innovation Forum in London did a whole session on plastics in the last month.

LikeLike